A short while ago, I explored the complex player moveset in Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash, a puzzle platformer released exclusively in Japan. If you have read that article, you would be well aware of my fondness for it – so it would come as no surprise that I follow it up with a discussion regarding its spiritual successor – Samurai Kid!

Biox, the developer of Samurai Kid, is probably most famous (or infamous to be more precise) for developing the critical flop that was Rockman World 2 back in 1991, the only Megaman title for the Game Boy to be outsourced by Capcom. Ten years later, Biox would release Samurai Kid on the Game Boy Color, the company’s final game before shutting its doors for good. It’s unfortunate that things turned out the way they did for the lesser known developer because Samurai Kid has all the hallmarks of a critical and commercial success. But for whatever reason, it struggled to find its audience. Thankfully for us Game Boy enthusiasts, that is not where this story ends. In September of 2021, marc_max released a patched version featuring a full English translation and Samurai kid has found a brand new lease on life ever since!

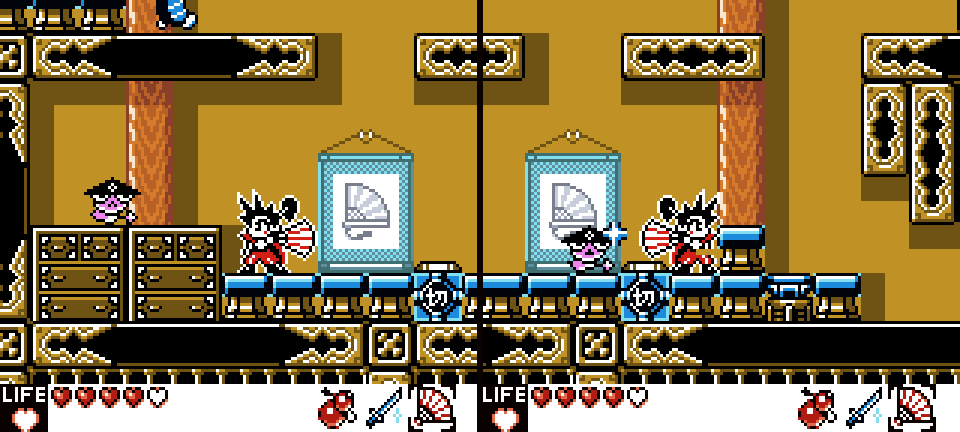

In every respect, it builds upon its predecessor with wonderfully detailed and colorful environments, fluid sprite animations and focused level design. All of which make it comparable to titles such as the acclaimed Wario Land 3.

At its core, Samurai Kid is much the same as Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash. You play as Homuramaru, the prince of Hinomoto. Hinomoto itself is on the verge of destruction thanks to the arrival of the Demon King and his army horde. Tasked with saving the kingdom from this new threat, you must solve various environmental puzzles and maneuver your way through ten massive stages using one of three different items at your disposal.

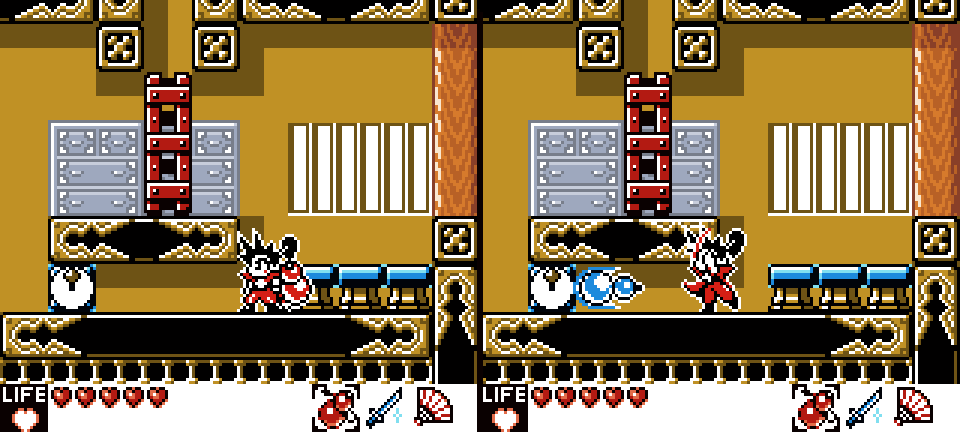

Where Gen the Carpenter had three different Carpenter’s mallets, Samurai Kid utilizes a gourd, katana and a fan, all of which serve a similar function to their mallet counterparts. Swinging the gourd at an enemy will cause it to turn into a block, which can then be pushed or smacked across the screen to manipulate switches. The katana can dispatch enemies easily and destroy blocks, thereby resetting the environmental puzzles when necessary. Finally, the fan will aggravate enemies, causing them to follow you, which can be used to your advantage when solving certain puzzles. Yes, on the surface, the two games seem to be more or less identical but while it does share many commonalities with Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash, Samurai Kid is so much more than a simple reskin.

For starters, the team at Biox have expanded the replayability factor substantially with the inclusion of unlockable abilities. Many of which will have the player returning to completed stages, accessing previously unreachable areas and retrieving collectable coins in an attempt to 100% the game. Furthermore, a speedrunning incentive has been implemented by ranking the player’s time at the end of each stage and scoring it accordingly, a feature I personally pined for in Gen the Carpenter.

If I had to pick just one improvement that really stands out to me though, it would have to be the inclusion of large ornamental Nobori (otherwise known as traditional Japanese wall banners) that are found hanging about in the backgrounds of the levels…

I suppose it’s a little strange to be so fixated on an art element in a level’s background. Given a moment to explain however, you will see this is actually an ingenious answer to one of the biggest problems that Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash failed to solve the first time around.

When I first played Gen the Carpenter, there was a point at which I could not progress for the longest time, and no amount of backtracking to see if I missed something seemed to help. I had come to a series of rocks with cracks in them, acting as a definite road block. It took me a little while to figure this out, but the game was asking me to learn how to do a very specific new move, and it was not about to let me progress until I figured it out.

This hidden but always available move was the ability to break partially cracked rocks by having Gen quickly spin around on his toes, twirling his hammer somewhat uncontrollably and smashing them up, thereby clearing a path through the blockage. To perform this ‘spin attack’, I had to roll my thumb around the D-pad in a clockwise manner a full 360 degrees and then press ‘B’ as if I were playing street fighter…

To be honest, this series of sequential button presses is a little too complex a move to expect the player to just figure out on their own, especially when there is nothing to hint that the hammer will break a rock in the game. These situations crop up periodically throughout Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash. Personally, I actually enjoyed discovering these new moves by process of experimentation (at least once I knew that was what was expected of me), but I am almost certain there would be a fair number of players that would have almost certainly dropped off due to frustration at points such as this.

“Drop-off” is the phenomenon where a player decides to stop playing a game as a result of one or more design decisions made by the developers of that game. In most cases, it’s because the game is just too hard or has become boring, but there are a plethora of reasons why this may happen depending on the genre and specifics of each game. It’s also highly dependent on the unique sensibilities and skill level of each player as well. In any case, the player has disengaged with the game and sees no reason to play any longer.

In the case of Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash, these ‘locked doors’ along the critical path of gameplay, which can be unlocked by learning some often obscure move through a series of complex button presses, may cause many players to lose patience to the point of putting the game down for good! It may take seconds, or minutes for the player to decide they have had enough but the risk of drop-off is there. Sure, the player could go on the internet and look up a walkthrough, but by that time, the damage to the players good will has been done by that point. It is up to the developer to make sure this doesn’t happen!

Okay then, why not just tell the player how to specifically play in-game? You know, overt signs with controller buttons printed on them or a dialogue box or two? You could do that, sure! But it’s not the most nuanced or elegant solution, and button prompts tend to break immersion unnecessarily. Most of all, something like a dialogue box loaded with text can have a negative effect on pacing, can be time consuming to read and cause the player to gloss over otherwise important information – even if the tutorial is coming from a cute talking animal or whatever it may be.

Wouldn’t it be great then, if there were some happy medium. Something a little more cryptic than a sign post with a string of button prompts on it perhaps, but also a little more helpful than hoping the player will just figure it out on their own. Then players like myself can work out what to do at their own pace, and those players that appreciate more help will at least have a clue to point them in the right direction!

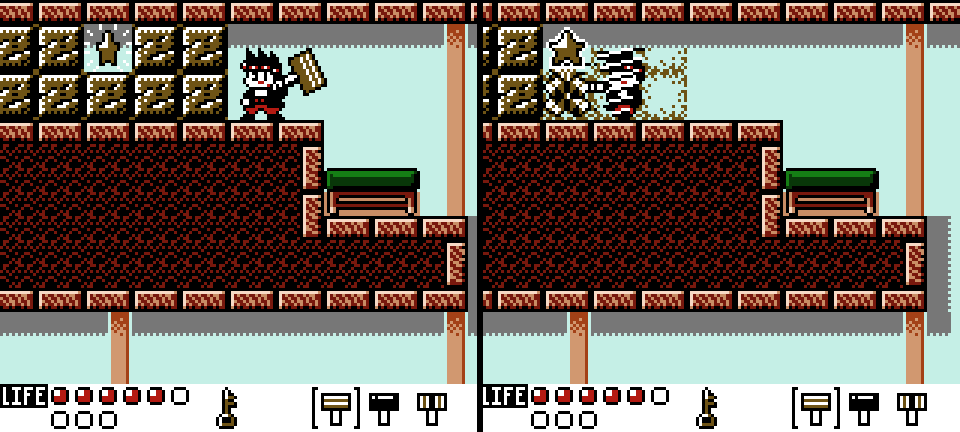

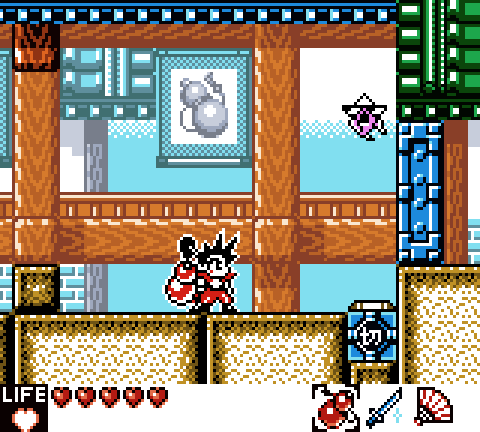

This brings us right back to the Nobiri hanging up in the background of Samurai Kid’s first stage. Although they are in essence a tutorial, they make sense within the context of their surroundings. Take a look at the first instance of the Nobori for example:

It sure seems like the right course of action is to wallop the enemy over the head with Samurai Kids’ gourd, right? This subtle hint is in keeping with the period style Japanese aesthetic and doesn’t put a pause on any gameplay while the player is learning the ropes and is presented in a way that doesn’t insult the player’s intelligence. This simple element is punching well above its weight class. It’s Pretty fantastic game design!

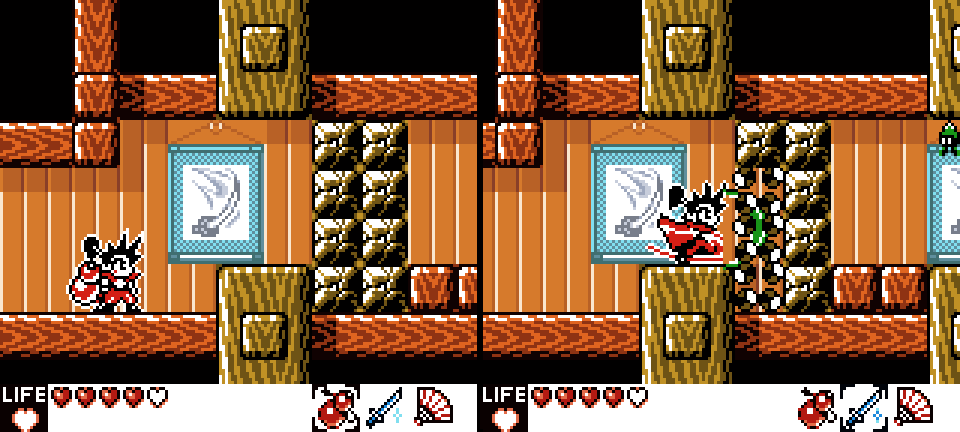

And what about the next instance:

Here we have the katana tutorial. What’s more, the player is presented with the same cracked rocks scenario as seen in Gen the Carpenter: Smash Smash Hammer Smash. This time however, the Nobori hints at using the katana to overcome this obstacle specifically! By pressing and holding ‘B’ for a few seconds, the player will learn they have a charged sword attack at their disposal and unleashing its fury will smash the rocks, unlocking the critical path forward. If that katana Nobiri was omitted, I wonder how many players would become significantly frustrated towards the game, having hacked at the cracked rocks with a simple swipe of the katana time and again to no avail?

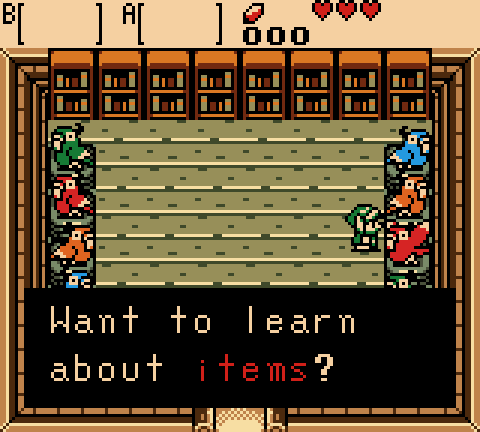

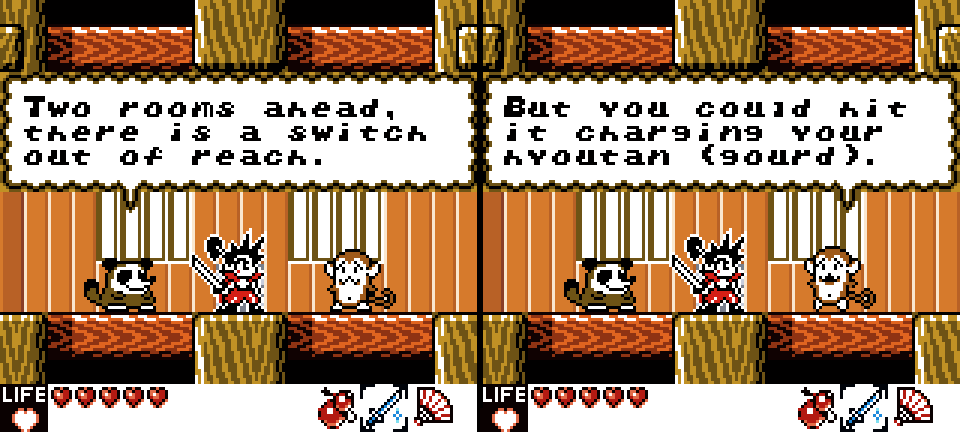

Okay, let’s move on to the next tutorial! Here we have… oh… oh no…

Looks like we have a tutorial coming from two cute talking animals! The pace has grinded to a halt so that Yasu and Hide can explain that the gourd also has a charged attack, this one useful for activating out of reach switches…

It’s interesting that there isn’t a Nobori depicting a gourd near the door shown in the image above. Especially when, at this point, the player knows holding ‘B’ and releasing it will perform a charge attack when the katana is selected. So it’s not exactly a stretch to expect the gourd to do something special when the same logic is applied to it. But perhaps Biox knows something we don’t as a result of playtesters feedback… Who knows? Yasu and Hide’s very wordy tutorial is the outlier here though, as the Nobori style subtle hint makes its return soon after to nudge the player towards discovering the function of the fan item (to coax enemies into following Samurai Kid).

By the end of stage one, the player will have learned many basic moves and a few of the more advanced ones at their disposal too. Excluding Yasu and Hide’s immersion breaking outburst at about the halfway point, the learning process has developed organically throughout the stage and it’s all thanks to some smart and considered use of background decoration.

Of course, the tutorial dialogue box will always have its place in many great Game Boy games. There are some things you just can’t teach without using the written word after all. But consider this; even when Samurai Kid wasn’t fan translated, those Nobori could be easily ‘read’ by anyone who cared to pick up the game, regardless of the language they spoke. There is a lot to be said about a well thought out, wordless tutorial!

Independent Games Designer, Artist, Film Enthusiast and Full-time Dad (he/him). Check out my games here!