In 1989, the Game Boy was unleashed upon the world and took it by storm. Over the next decade and a half, until the last officially licensed Game Boy Color game was released in 2003, more than two thousand titles found their way to the two Nintendo handheld consoles. That is a lot of games and, when it comes to development, much can be learned from them.

We will be regularly looking back on the game catalogue of the Game Boy and Game Boy Color; casting a magnifying glass over classic games, hidden gems and forgotten masterpieces and highlighting what about their design made them great!

So where do we start? Well, I would argue the logical place is the very first game to be released on the original Game Boy; Super Mario Land! In fact, we will be looking at a single aspect of the trilogy at large, and from this, revealing a fundamental principle of level design.

What do the opening screens in the first levels of the Super Mario Land trilogy have in common? Hint: It’s not Mario.

They all have nothing in them!

This is common throughout the entire Mario series. From the opening screen of Super Mario Bros on the NES, to the exterior of Peach’s Castle in Super Mario 64, to the starting location of the Cap Kingdom in Super Mario Odyssey, and there is a really important reason why the level designers chose to do this; to allow the player to explore how Mario or (in the case of Wario Land) Wario moves – without any negative consequence.

Let’s take a closer look at each screen per game.

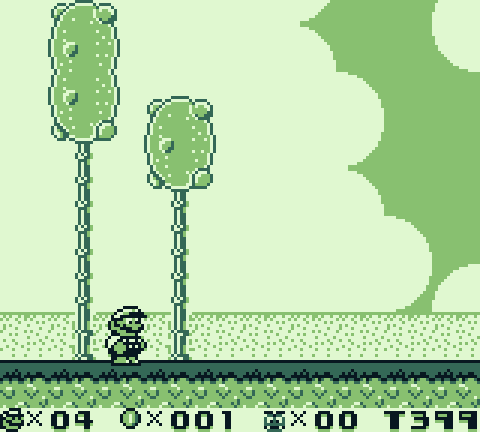

I suppose I told a little bit of a white lie when I said Super Mario Land’s opening screen has nothing in it. It has almost nothing in it, but the point remains the same. There are no enemies to get in your way, no pits to fall down, just one single unbroken platform that extends across the entirety of the screen, a pipe to Mario’s left and a question mark block directly above him.

Both the large open space to Mario’s right and the pipe to Mario’s left both subtly imply that the player should begin moving towards the right of the screen (The direction of the goal). While the mysterious and enticing question mark block encourages the player to experiment with button pressing and, in turn, the player will learn that Mario can firstly jump, and secondly, hit the question mark block from underneath, thereby being rewarded with a coin!

While players familiar with Super Mario Bros on the NES (which came out four years earlier) will already know that the player should head right, and how the question mark block works, Super Mario Land’s unique physics engine will still be a complete mystery to them. This single platform – devoid of any other obstacles – provides a safe space to explore Mario’s basic movement and allows the player to experiment with buttons before attempting the first level in earnest.

Super Mario Land 2’s opening screen is the most pure of the three games. It has literally nothing in it but an extended, unbroken platform. In fact, this minimalist design continues for a further two screens before we see an enemy or question mark block at all. Why? Because the designers want the player to not only familiarize themself with Mario’s basic movement but also explore the relatively more advanced sprinting mechanic too – all in complete safety.

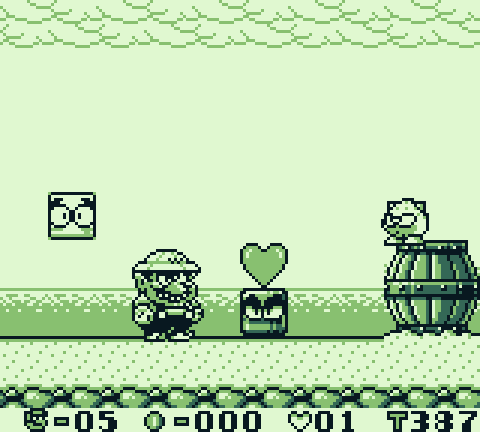

Finally, Wario Land’s opening screen design sits somewhere in between the first two entries in the series. Again we see the familiar extended, unbroken platform, but this time the designer has placed Wario Land’s equivalent of a question mark block in plain sight to the far right of the screen. It is doing the exact same thing as the pipe to Mario’s left in SML and the open space to Mario’s right in SML2 (asking the player to investigate whatever lies to the right of the player character).

The block also raises a question in the players mind; ‘Can I break that block? And what happens if I can?’. The player will head towards the block, experiment with buttons and movement, learn Wario can jump by pressing ‘A’ and body slam by pressing ‘B’, then (hopefully) apply all that knowledge by jumping and breaking the block from underneath! Just as the question mark block rewards the player with a coin in SML, so too will this block reward the player with a heart (an item tied to gaining lifes in the game).

This design strategy is a fantastic way to teach the player how the game works intuitively without the need to explain anything with words, and by keeping the vicinity free of hazards, the player can focus entirely on learning the basics without fearing negative consequences!

Wario Land continues this process further in the next screen too. It presents the same block a screen later, but this time it’s not in the air – it’s on the ground. Obviously, Wario will not be able to break it using the same jumping method but the player now knows that these blocks deliver a reward when hit. The end result of this design choice will have the player experiment with Wario’s controls until they find themselves body slamming into the block and collecting another heart. The player has now learned the basics of Wario’s moveset using elegant level design and the subtle power of suggestion!

In all three of the Super Mario Land titles, the designers have focused on allowing the player to learn how the game works through experimentation, play and intuition by removing all threats and delivering a safe space to move freely in the first moments of gameplay. SML2 and Wario Land place heavy focus on low risk gameplay throughout the whole of their first levels, both of which contain not a single death pit at all.

The Super Mario Land series shows us that removing threats such as enemies, obstacles and instant death pits in the initial stages of gameplay allows the player to become comfortable with the mechanics and functional aspects of the game’s design, and to prepare themselves for the challenges to come.

This philosophy need not apply only to platformers, of course. Players can profit from a safe, risk free space to explore the intricate behaviors and mechanics of any game genre. Whether it’s fighting a wooden dummy that can’t fight back in a complex RPG battle system like Undertale, or setting the speed of gameplay to a snail’s pace in a puzzle game like Tetris, it’s clear that nothing can mean everything to a player in those first moments of gameplay.

Independent Games Designer, Artist, Film Enthusiast and Full-time Dad (he/him). Check out my games here!