Chris Totten has had a long career in gaming. He is currently working on two new indie titles, Little Nemo and Nightmare Friends, and is the developer of the GB Studio title Kudzu. He is also in the Animation and Game Design program at Kent State University in Ohio. “I’ve been making games since about 2006” he starts. “A friend of mine in college first said: “Hey, you are good at art, and I can program – let’s make a game together!” and these turned out to be famous last words! “We didn’t make much beyond some simple demos, but I began learning game development on my own. After finishing architecture school in Washington, DC, I also started collaborating with people in our local International Game Developer Association (IGDA) chapter, which led to more game-developing opportunities on a bunch of mobile, educational, and ‘serious’ games. I also founded my own company along the way, Pie for Breakfast, for putting out more entertainment-focused games. Long story short – now I’m here!”

It’s Chris’ love for architecture he explains is “very much at the heart of both how I design and teach games. For design, I try to be very aware of how players move through space, how what they see influences their actions or decision-making, how to orient players in space, etc. The history of architecture also serves as inspiration for things like storytelling or environment art, for example, my GB Studio game, Kudzu, has quite a few characters and locations inspired by architectural history. In teaching, I’ve a very project-oriented approach, so we learn design theory, we then test it through its application in design projects. In this way, we can take even tutorial projects for learning software, then make them ‘about’ showing mastery of non-software game design concepts. I’m biased in this area, but I think game design and architecture are very much allied disciplines.”

Chris applies these ideas to his GB Studio development and is keen to point out why it’s such a good tool for his students: “GB Studio is a fantastic teaching tool! Where do I even begin? First and foremost, it makes game-making achievable for students. When you use big engines like Unity and Unreal, they take a lot of practice and expertise to master. It also takes a lot of time, people, and resources to make really big, expansive games. GB Studio helps you make that Metroidvania or that action-adventure game you’ve dreamed of if you’re willing to imagine it in 8-bit and at a Game Boy resolution. Since it doesn’t require much actual scripting apart from the visual scripting tools, it can be a nice starting point for people for whom scripting is intimidating. It’s also a fantastic tool for teaching students to work within limitations. While they may not be making Game Boy or homebrew games throughout their career, they will probably have to make a game for a phone or a console like the Switch. In that way, it gets them away from the unlimited ‘blue sky’ thinking of making games for the machines in their computer labs, which are usually very beefy and capable. Overall, they learn how to get the most out of a small space.”

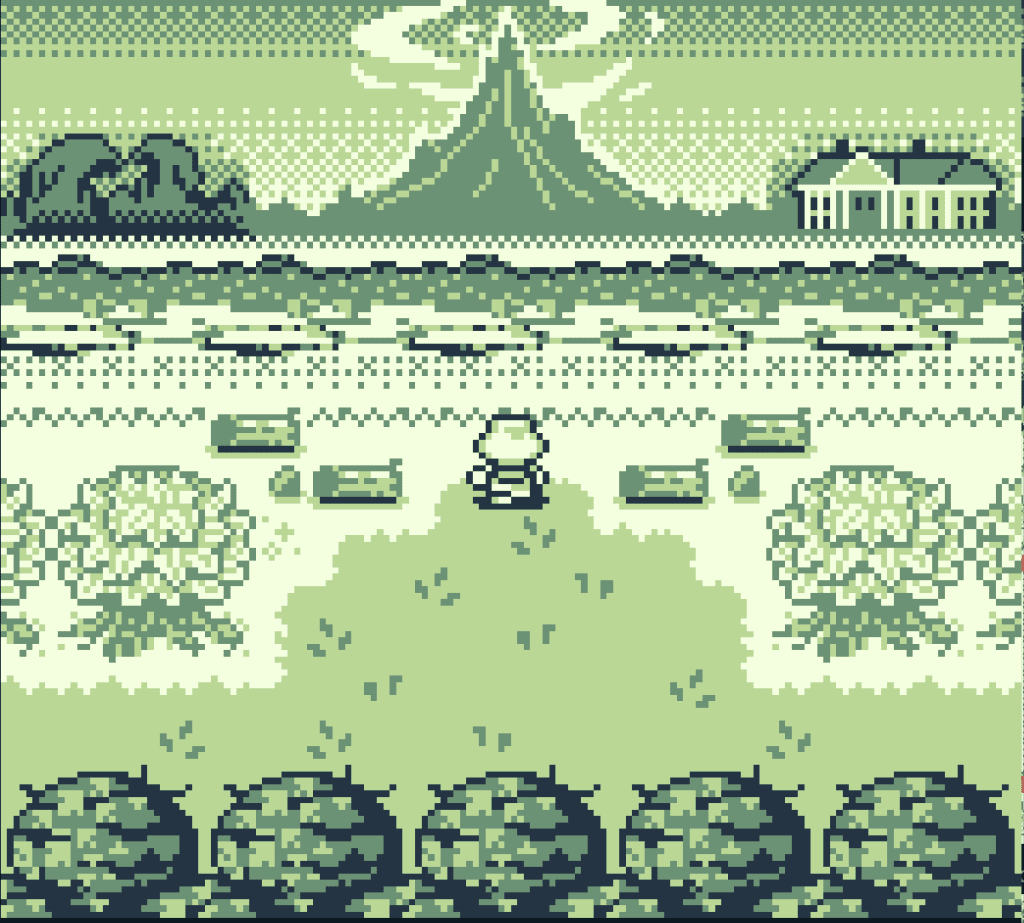

Chris designed his own GB Studio title, Kudzu and tells us about its development: “I started the game in 2020, which I want to emphasize because I want folks reading this to know just how long a project like Kudzu can take. The game takes me about 6 hours to play through (as the person who knows where everything is), so a game like that, even in something that makes your project scope super lean like GB Studio, still takes a significant commitment to make. That all being said, that achievable scope is exactly why I wanted to use GB Studio. I downloaded it after seeing a story about the engine on a gaming news site, and it just lived on my desktop for a long time while I said ‘Someday I’m going to open that and learn it.’ Finally, during lockdown, I opened it and decided to piddle around. After trying a few things, I realized how powerful it could be and 2.0 was just about to come out, so I said, ‘Wait, I’ve had this idea for an action-adventure where you fight off kudzu vines forever, if I make it in something like this, I might actually finish it! It was still a MASSIVE undertaking, but here we are!”

The game features lots of references to plant life, and Chris explains the work experience that started the idea. “This is something to come out of architecture school. During my junior year, one of our projects was a ‘scholar’s retreat’ on a new piece of land my university acquired. When we toured the site, we saw a field of what we thought, as a bunch of kids from the northern U.S., was ivy covering a big portion of the land. Most of us in my group centered our designs on this feature of the site, with me designing my building with a patio that extended out into it, and other classmates of mine making hedge mazes and the like. I presented first in my group during the final design jury. Our school’s assistant dean, who was one of the external reviewers, told me that it was kudzu, which is an invasive plant that covers and chokes out other plants, and asked why I would celebrate something like that in my design. At this harsh critique, the rest of my group went white, because we’d all used it, but my instructor stepped in and added that even he didn’t know what it was, so we should proceed without assuming that all of our designs would be swallowed within a week of construction. I’m still friends with both of these professors by the way – critique like that is just part of the job!”

This experience then led to the idea for Kudzu as Chris explains: “Years later, I was telling my wife this story, and she mentioned that her brother used to fight off vines like that in their backyard with a machete, so we thought it would be fun to make a game where he was fighting off evil kudzu. We also have a love of gardening, so bringing some of these stories and hobbies together was where the plant theming came from.”

While Chris was the main developer for the project, he did have some help along the way: “I did a lot of the primary development for the game, but my collaborators included students of mine who can participate in projects like this thanks to my school’s internship program. A big thing we try to emphasize is not just learning to use the software used to make games, but having students develop games and put them out into the market for real, students at my school own their own work, so have the freedom to monetize it. For this, we try to find ways for students to collaborate on commercial game projects or games used for real-world impact or ‘serious games’. In this way, we’ve even had students have games they’ve made for classes published commercially!”

Kudzu is a beautiful game and Chris explains the influences other games had: “I wanted the game’s presentation to feel really authentic, so I looked at a lot of the key art of Game Boy favorites like Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters, the Super Mario Land games, and of course, Link’s Awakening. Despite all these callbacks, I wanted the art to help it feel like it was joining that lineup as a new game and IP for Game Boy, even if it’s in a familiar genre, rather than just being a collection of callbacks.”

It wasn’t just the art of other Game Boy titles where Chris found inspiration either: “One of my biggest design influences has been Takashi Tezuka who was the director of Link’s Awakening and Super Mario Bros. 3 and most recently producer on Super Mario Bros. Wonder. I’ve always admired how he can take design ideas and stretch them to their limit, often mixing and matching them with other ideas to make something really cool out of a small kit of parts. Trying to put myself in that headspace was really helpful while building Kudzu.”

The game was picked up by retro publisher Mega Cat Studios after a chance meeting: “The game is being published by Mega Cat Studios, who have showcased their games for many years at a festival I co-founded at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) called SAAM Arcade. I ran into them at a convention in Columbus, Ohio and showed them Kudzu after chatting for a bit. We thought it might be a good fit, so decided to work on it together. They likewise helped connect me with the game’s composer, Brandon Ellis who also worked on 30XX, Catlateral Damage, and a bunch of other cool stuff, and helped organize making physical editions and other merchandise.”

Kudzu was crowdfunded and we asked Chris if this added any extra pressure, knowing Game Boy fans have paid money upfront: “Crowdfunding is great for getting money to work on projects and visibility, but also makes you more accountable to an audience than you normally might be on regular social media. In the case of Kudzu, we crowdfunded mostly after the game was finished so there wasn’t much to do on that end, but you do have to do things like build art books and other merchandise, that you might not otherwise have to. With the other game I’m working on, Little Nemo and the Nightmare Fiends, we crowdfunded much earlier in the project as a way to build up our ‘vertical slice’ with the early version of a game that you show to publishers as proof of concept, and for that, we have to update backers frequently on the state of the game, but also have to be clear on what the priorities of the project currently are. It’s mostly game development vs. merchandise, both of which take a lot of your attention.”

Chris explains what makes GB Studio a good tool for making games such as Kudzu: “It makes games like Kudzu way more achievable for one person or a small team. Big, exploratory adventures are high among the ‘wish list’ games people want to make when they start making games. The usual advice is to make small things like a shooter or other arcade-like experiences since they show you how long even simple things take. That advice still holds up and I tell new devs to make small things even in GB Studio, but the resources required to make a respectable adventure are much lower, especially if you don’t do real-time combat. It takes a lot less time to get to something really impressive, especially if you don’t do color, although doing color is still good, it adds the extra step of coloring it vs. focusing on the green/gray palette.”

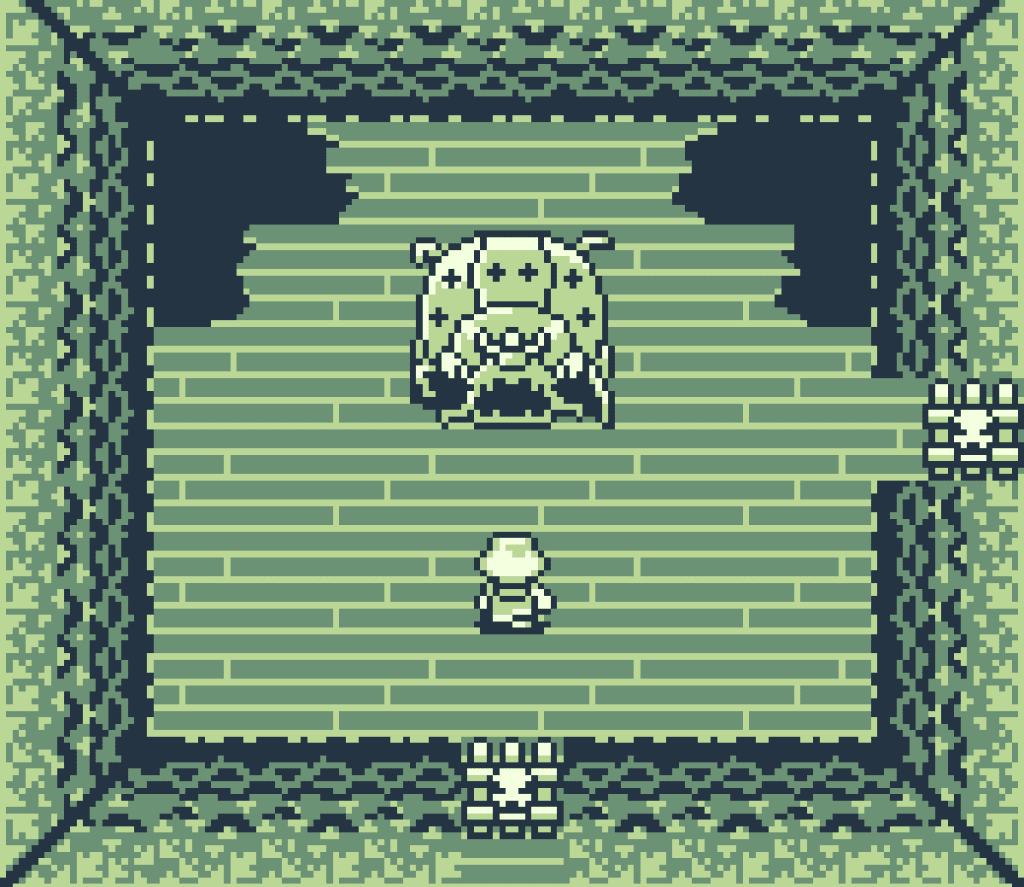

When asked what the main challenges are in making a game like Kudzu, Chris points out several issues: “Well…I decided to make a video game. That was my first mistake…Seriously though, every game that is released IS a miracle, these things are so hard to make. First was the scope of the game itself. I have talked a lot about how GB Studio and sticking with the regular Game Boy as the target platform saved a lot of time working on the scope, but a Metroidvania is still a Metroidvania. Beyond the sheer amount of content, you also must carefully plan and test the progression for levels like that so that they can be engaging, understandable, exciting, and deliver a reasonable difficulty curve. Once a world becomes continuous, there must be a lot more planning vs. when you make self-contained levels like those found in a Mario game. I learned so much making this style of game that I’m even going to write a whole new level design book, in addition to the other two I’ve published, about it just on action-adventure design and it’ll have GB Studio tutorials in it.”

It wasn’t just the design that proved challenging, updates to the tools caused an issue: “I also started the project in the Beta 2.5 version of GB Studio. By the time 3 came out, I was far enough along that I would have had to remake the whole game up to that point. I’d tried porting it, but there were issues that I couldn’t even resolve after talking through them with the GB Studio development team. This meant that I had to take extra steps to do things like bosses made from big sprites. I tried the popular plug-in that was going around, but couldn’t get it to work reliably, and I didn’t have the same tools to deal with things like memory leaks that folks developing in 3 have. I had to get creative with wringing the most that I could out of 2.5 and, despite some bugs that still persist, like one of the bosses having sprites that split apart in a minority of playthroughs, I’m really proud of what I was able to pull off.”

Finally, we asked Chris how he feels as Kudzu gets closer to launch: “Excited, but absolutely terrified. What if the design is too retro? Not retro enough? What if a YouTuber with 200K followers hits one of the animation bugs on their playthrough or even a crash bug I missed in all my testing? Murphy’s Law has a habit of striking in that way! What if it’s too niche? Did I put too much of myself into this? I’ve checked the text extensively, but what if I missed a typo? The tough thing about releasing a game in this way is waiting. When you release a game on something like itch.io, you can finish it and then post it right away. The response is more immediate, so you don’t have that extra time where you start thinking ‘Hmm…maybe I should go look at this part of the game again…’ At some point, you just have to decide to stop working on it and be at peace with the ‘it’ that it is. Releasing games can really stress you out in ways you don’t expect, even if you’ve been through it before!”

There are lots of positives though as Chris explains: “At the same time, it’ll finally come out and people can finally see all the things that make me excited about it! I’d be really excited if people like it and go through a lot of it. I tried to add lots of fun characters and ideas throughout to keep folks engaged like a rather dashing late-game boss blending elements of Metal Gear Solid 3’s The End and Heiankyo Alien. I think the main villain is one of the most fun characters I’ve worked on – my daughter just loves drawing fan art of her. Just as we brainstormed for this game, my wife and I have already brainstormed a lot of ideas for if there’s ever a Kudzu 2. If it succeeds, I’d love to see what’s next for some of these characters. If nothing else, every game you work on is still a meaningful experience and set of lessons, so I have a lot to chew on for Little Nemo and other eventual projects.”

Thanks to Chris Totten for sharing his thoughts on this interview. Kudzu is now available for pre-order on Switch courtesy of the folks from 8-bit Legit, and will be released on physical cartridge from Mega Cat Studios.

Happy go lucky game journalist, write for print mags, books and online. Love my retro and have a taste for new GB games.