Common Thread

Thread events are one of the newest additions to GB Studio, and with no documentation to explain how to use them effectively, there has been a lot of confusion as to what they can and can’t do. At their core, they are the functions running behind the scenes, starting and stopping events and executing other scripts. With the release of version 4.1, we now have direct event-based access to them, so let’s dive into the ways they operate and how they can make your game’s scripting even better.

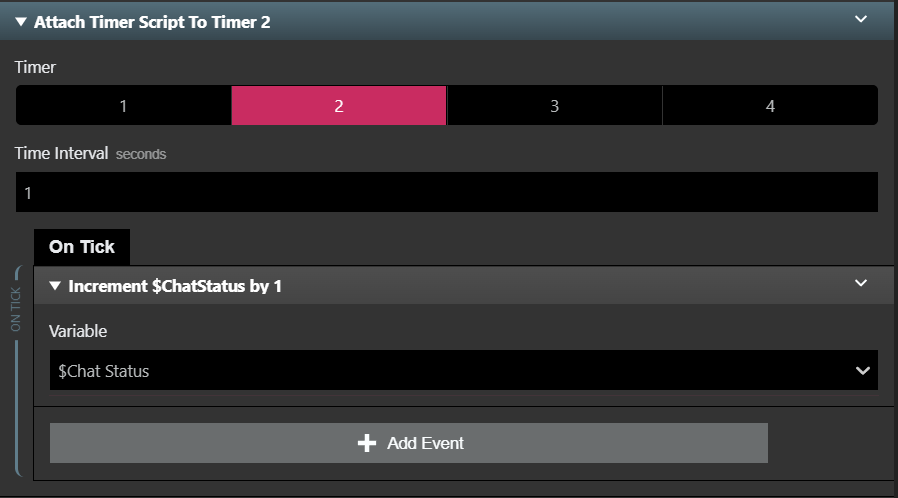

To properly understand what the Thread Start event can do for you, we should look at some of their close relatives first. Timers and the Script Lock and Script Unlock events are very similar in nature to how Threads work. Each of these events can do some amazing stuff in context, but they certainly have their limitations, which you may or may not be familiar with. Since Attach Timer Script is the event closest to what we can accomplish with Thread Start, we’ll look at that one first.

Timers are a great way to run code periodically, based on a set timer amount. They execute the entire script every x amount of seconds or frames, depending on what you choose to define them. However, one of the biggest flaws of Attach Timer Script events is the inability to remove the Timer once it has already begun executing the script you assigned. It remains inaccessible to cancel those functions until they are complete, somewhere out in the digital aether. Because of that fact, using Timers in some projects is quite frustrating, so the best practice is to make sure you limit the length of what is being executed on any of your Attach Timer Script events. Since Threads are tied to a variable and executed based on that variable’s value, they do not have this limitation.

Next, we have Script Lock and Script Unlock, which are two of the most useful events in our repertoire, especially when you are looking to set up cutscenes and ensure the player or other actors are unable to move in the meantime. These pause and unpause all scripts, restricting player movement, On Updates and more, until the execution of the script you locked is unlocked again, or the script finishes.

Locking ensures that you have exclusive access to what is happening with your code and it executes as you desire, but Script Lock and Unlock have to be meticulously planned to ensure that exclusive access. Unlike Threads, these events by themselves are not their own scripts, requiring you to place them within another script, whether it’s a custom script, in an actor’s On Update, or a Thread Start event itself.

Now that we know a bit of how Threads relate to these other events and what they can do, we’ll look at the Thread Start and Thread Stop events in detail and get into the nitty gritty of what they can and cannot be used for.

Weave Nothing Behind

Threads are scripts that run similar to the built-in On Init or On Update scripts, but they can be called at any time. They also execute from top to bottom, which is the same as any other script filled with events, and can even run simultaneously, if started one right after the other from the same source. While there are a lot of things Threads can do, we should touch on what they are limited by to help set expectations.

First off, Threads don’t naturally run continuously. I could think of a lot of situations where that would be nice if that was built-in, but many more where I am thankful that they don’t. They are typically intended to be a one-off script execution, but that’s not to say that they can’t be continuous, it just takes a bit of effort.

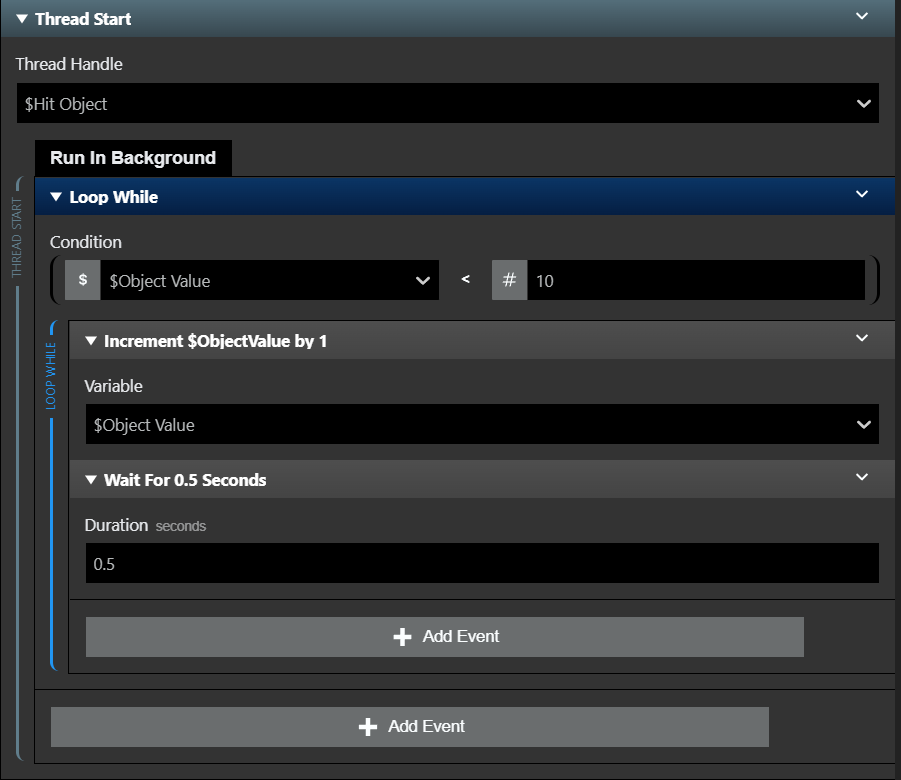

To run a Thread in the background over and over, you will need to utilize a Loop event inside of it. Loop for and Loop While events are the most commonly used, but if you’re utilizing a lot of variable values for determining how your Loop event runs, you can use a Loop While Math Expression event too.

While it’s looping, the Thread event will continue running in the background until you either give it the condition needed to stop, or use a Stop Thread event. Keep in mind that as long as you are running a Thread, it’s the same as having another constant script from an actor running in the background, so stop it when it is safe to do so, if not only to help with performance but also to help you stay organized. Thankfully, threads don’t continue to run after finishing running through their events or when switching scenes, so doing so will automatically stop all running threads.

Because Threads utilize a unique variable, it is best practice to set a couple of them aside for exclusive use with them. Naming them based on what they do might be an easier way to keep track, for example: “Soldier 1 | Thread” and “Soldier 2 | Thread.” If you try to use one variable for multiple Thread events, you will quickly find out how they fight for priority and this will mess up your execution order, including stopping events unintentionally. It’s best to play it safe and either set them up with Local Variables from where the Thread event was called, or set up Global Variables to use.

Two Threads Are Better Than One

One of the best features of Start Thread events is the ability to run them simultaneously. Instead of relying on the order of sequence when setting an event to true and praying that the actor On Updates pick up the command at the same time, you can simply start threads one after another and sync them up that way. The best use for this convenience is having multiple actors moving at the same time.

Often when you have cutscenes running, you want to have multiple things moving at the same time. With Threads, you can now achieve this with a level of control that we did not have before. A couple of examples would be having two NPCs walking side-by-side, or complex animation sequences for visual effects. There are a lot of uses for this feature, but it’s up to you to figure out what works best for your game.

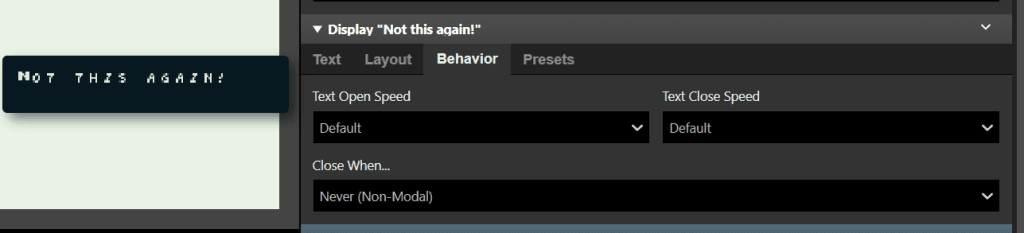

It’s worth mentioning that even though Threads are a dream come true for a lot of developers utilizing cutscenes for a cinematic approach to their games, Threads cannot run while a modal event, such as a dialogue box, is running. To get both to work, you would need to ensure that the dialogue box is set to non-modal, which means it will not close when it is done rendering the text inside or react to a button press.

You can then close this box with either the Close Non-Modal Dialogue or Hide Overlay events, which you can add to any button with the Attach Script To Button event. If you wanted to add the functionality back to using a button press to close the dialogue box after it finished typing out in the box, you could use either an Attach Timer Script to set a wait time or Thread event with a Wait Event to add the ability to close it with a delay. This also gives you the long-awaited ability to set up a button that allows the player to skip cutscenes that run in the background, and then you can remove that functionality on the next Attach Script To Button event. It’s tricky, but most of the cleverest means of doing something are.

Tying It All Up

Once you have settled on a means of handling your Timer scripts and Buttons, it would be wise to encapsulate that code into a custom script if you plan on using it throughout your project. You cannot access any actor other than the Player if you place a Thread inside of a custom script, however, so plan accordingly. This is something I call double-nesting, as the engine does not provide access to actors this way. You will notice you have the same limitations for Attach Script events as well, but these can be placed in an On Init script and still have access to other actors.

My last bit of advice regarding Thread events is to use them as “dropped code.” To explain this better, let’s look at triggers. Triggers execute events in order and freeze everything going on in the scene until they are complete. Let’s say you want the player to be able to use the trigger as a button to move a block in the background, but you need to show some visual effects to really sell the sequence. If you added anything with a time-based element, like a Camera Shake event, or a literal Wait event, the scene and more importantly the player actor will be frozen in time, leaving them unable to move.

Instead, you could use a Thread Start event to “drop” this code within the events of the trigger and leave your player able to continue moving through the zone. These are also quite useful when executing code from On Hit events, especially long sequences of code. It’s situations like these that really allows the use of Thread events to shine.

Threads are a great new tool that allow us to do some amazing things. They are familiar to other scripting tools that we already have access to, but allow even more freedom to script things with precision and care. Why not give them a try by implementing in either your current project or your next one and see how much easier they make the scripting process.

Writer, Game Designer, Engine Bender, Retro Enthusiast. Co-creator of In The Dark. (He/Him)